Stephen Curtis married Belle Willard and they were separated after many years of marriage during which they had the four children listed, Grace, Mavis, Doris and Wallace. Grace married William Weber and they had two children, Frederick and Reginald, after which, while she was still young, William shot and killed her. He was acquitted in court, but there is no doubt in the minds of those who knew about the circumstances, that it was a cold-blooded murder. He was a German, born in Germany, and regarded his wife more as a chattel than as a companion. He was hard and cruel, taught his little boys to endure without crying such torments as being lifted by the ears, was very cruel to his wife during the years she lived with him, and her life was a very unhappy one. They lived in Grand Rapids.

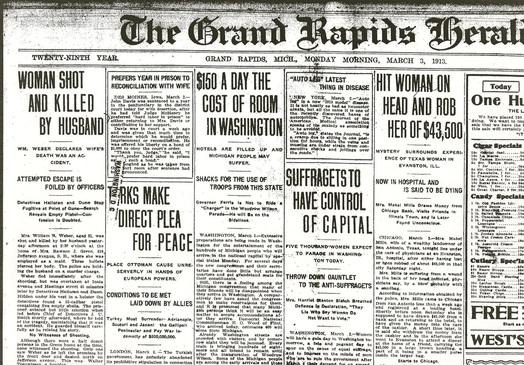

After I discovered how much the internet could contribute toward researching my family history, I decided to try to find out if this story was true, and when and where it happened. First I went to the Western Michigan Genealogical Society database page and searched the Western Michigan newspapers, which covers 1910 to 2011. There was only one entry for Grace Weber, which was an obituary published in the Grand Rapids Herald on 3 March 1913.

Being on a budget, instead of ordering the obituary for $5 from the Western Michigan Genealogical Society, I requested it as an interlibrary loan from my local library system. In a few weeks I received a copy of the front page of the Grand Rapids Herald for Monday, March 3, 1913.

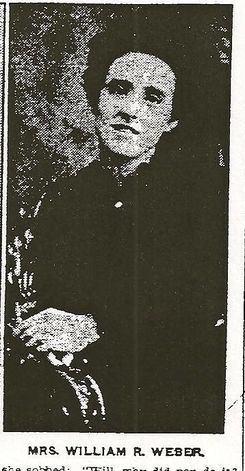

I knew the story didn't end there, so on my next trip to the Library of Michigan in Lansing, I read through several weeks' worth of microfilmed issues of the Grand Rapids Herald. I was rewarded by a photo of Grace and a mug shot of William.

(Grace Curtis Weber was born in Michigan in November 1881, the daughter of Stephen and Belle Willard Curtis. She married William R. Weber, who was 16 years her senior, on 19 Feb. 1905 in Battle Creek, Michigan. William was born in Germany in 1865, and had been married once before. They had two sons, Frederick (Fritz) and Reginald, who were 7 and 5 years old at the time of the shooting.)

Grand Rapids Herald, March 4, 1913

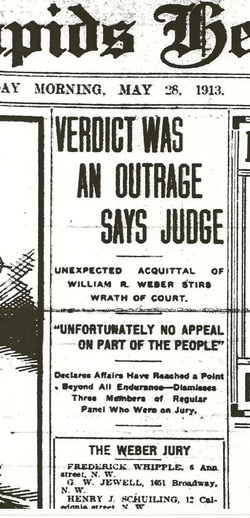

William R. Weber, charged with the murder of his wife, was declared not guilty by a jury in superior court which for the last two weeks has been trying the case. The verdict was rendered at 10 o'clock yesterday forenoon and jury and respondent were promptly discharged.

But so far as the court was concerned the case did not end here. Showing his anger and disgust in every word, Judge Stuart bitterly arraigned [sic] the jury for what he termed an outrage upon the city of Grand Rapids. He followed this by excusing three members of the regular panel who had been upon the jury because he said he did not think they were competent to try cases in court.

Verdict Was Absolutely Unexpected

The verdict was unexpected by practically every man and woman in the big crowd in the courtroom. E.N. Barnard, attorney for the defense was perhaps the only man who really felt confident all through that he would win. When the words "not guilty" were pronounced by the foreman of the jury, something like a gasp of astonishment swept around the room. Weber dropped into his chair and sobbed a moment and then began shaking hands with his friends and tried to shake hands with the court.

For just a moment, Judge Stuart looked the jury over then he turned loose the things which had been accumulating within him.

"Gentlemen," he began, "this is an outrage upon justice in this community. Aside from all other considerations, you have taken the story of the respondent as entirely true. You apparently have had no regard for what any one else has said or of the surrounding circumstances. I am frank to say to you that this community has been outraged by such a verdict and I cannot but express my feelings to you at this time.

"Unfortunately, there is no appeal on the part of the people. The verdict must be accepted, but I do hope that if this system of wife-shooting without

punishment continues in this city the people will awake to the fact that something must be done to insure certain punishment for crime and that every story told by a respondent in a courtroom cannot be accepted as a fact.

"I might suggest that men contemplating the shooting of their wives usually do not take two or three witnesses with them. Gentlemen, if this verdict is your view of justice I differ with you very decidedly."

And there were several outraged letters to the editor, one of which, from Mrs. Mary E. Hay, ended with:

"The cruel injustice of the whole thing, a devoted mother lies in her grave, two sweet children robbed of their mother, and the man that carried a loaded revolver walks the streets a free man."

As a genealogist, I am devoted to telling my ancestors' stories. And as long as I tell stories such as this one, of Grace Weber's untimely death, my ancestors will live on.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed