And so should you.

|

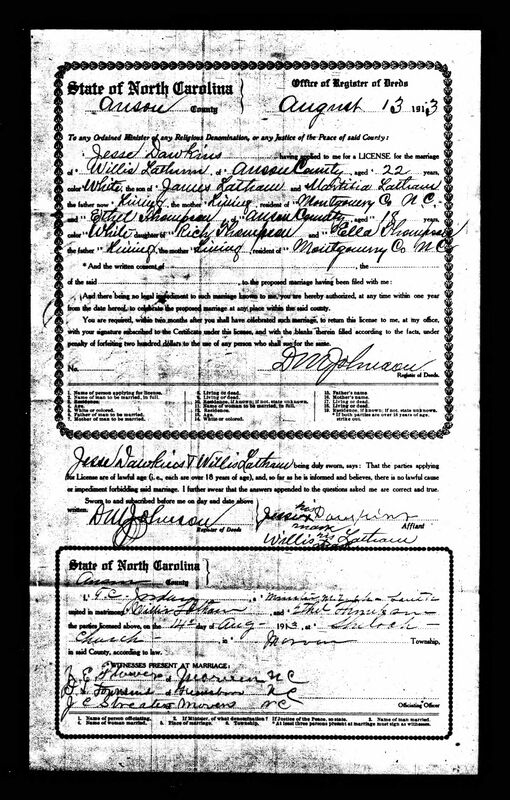

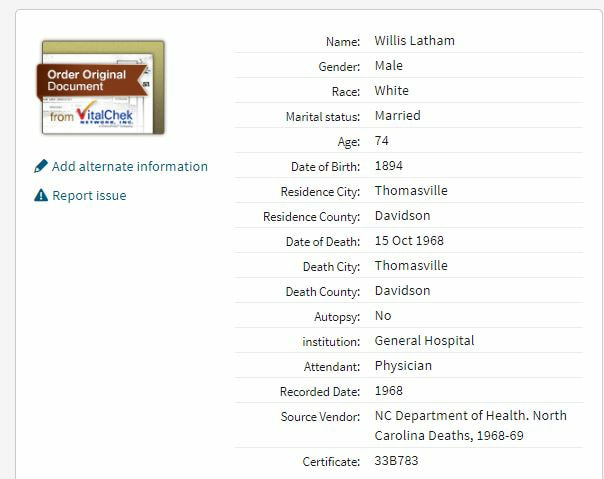

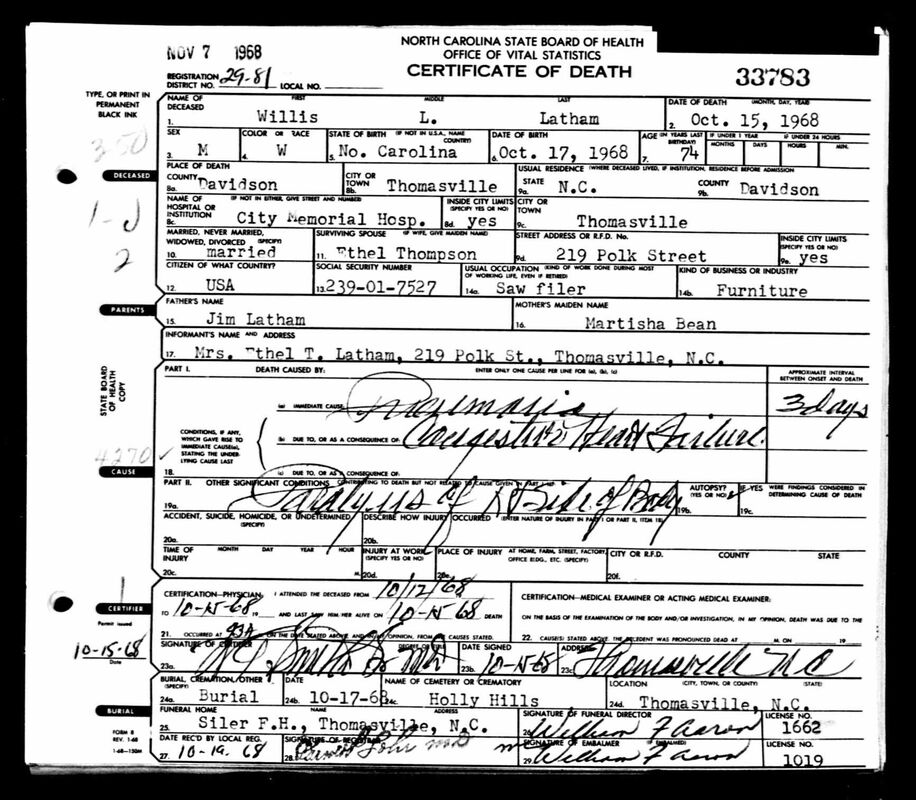

I'm writing a family history for a client with deep roots in North Carolina, and came upon an interesting record the other day. My client's great-aunt, Ethel Thompson married Willis Latham in 1913 in Anson County, North Carolina. "North Carolina Marriage Records, 1741-2011," Ancestry > Anson > Marriage Licenses (1870-1961) > image 5856 of 11533, Anson County North Carolina, marriage record for Willis Latham & Ethel Thompson (1913). For this family history, I needed to provide the dates of birth and death for Willis Latham. The 1900 census told me that he was born in April 1894, and the North Carolina Death Index on Ancestry stated his date of death as 15 October 1968 in Davidson County, NC. Ancestry provided no hints for Willis Latham pointing to his 1968 death certificate, and none of the other family trees containing him had his death certificate. Where was it, and why wasn't it showing up? I used the browse feature in the database, heading for Davidson County, then 1968, then October. As I expected it to be, Willis Latham's death certificate was there. Once I saw it, it was obvious to me why Ancestry's computer-generated hints didn't catch it. His date of death was correct, all right: 15 October 1968. But his date of birth was two days later, on 17 October 1968. Obviously someone typed in the date of burial in the wrong box. "North Carolina, Death certificates, 1909-1976," Ancestry > Davidson > 1968 > October > image 29 of 54, death certificate 33783 for Willis Latham (1968). I should state right here that I NEVER accept Ancestry's hints without checking them first. I've seen hints for christenings in London, England in 1795 when the person of interest was born in Nebraska in 1911. And if there are records that should be on the hint list, and aren't, I go looking for them.

And so should you.

0 Comments

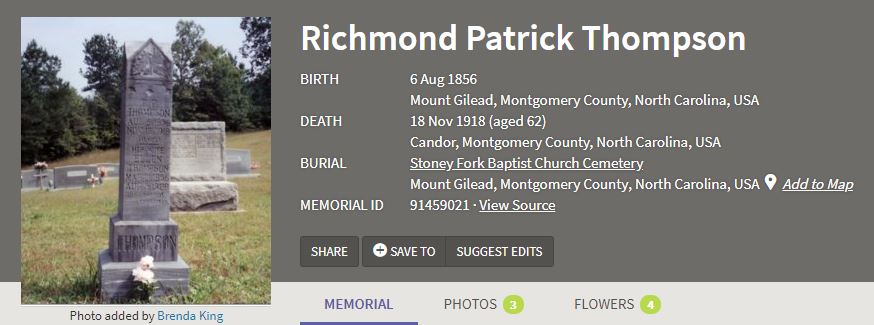

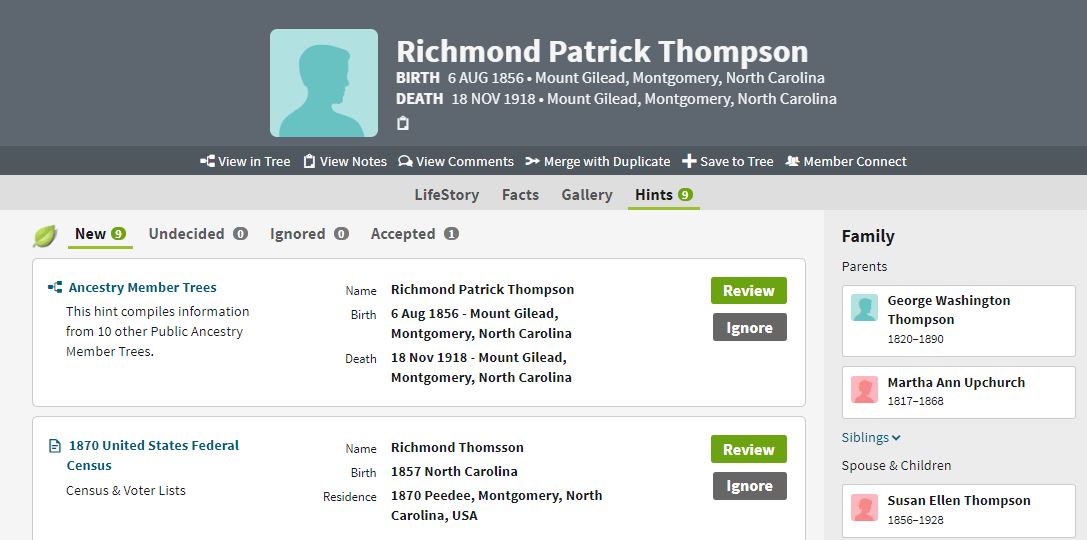

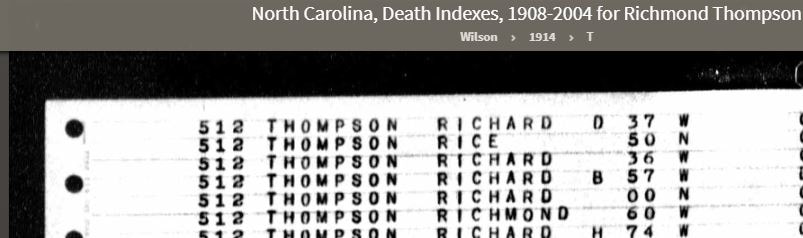

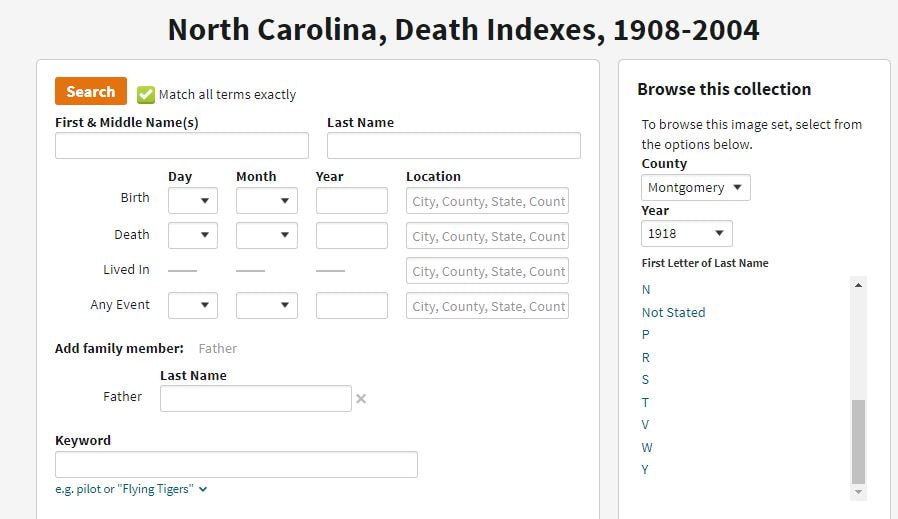

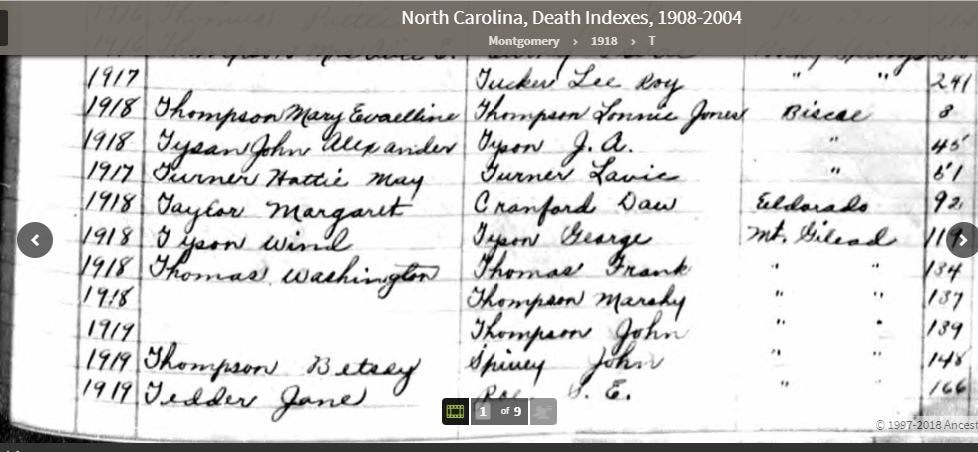

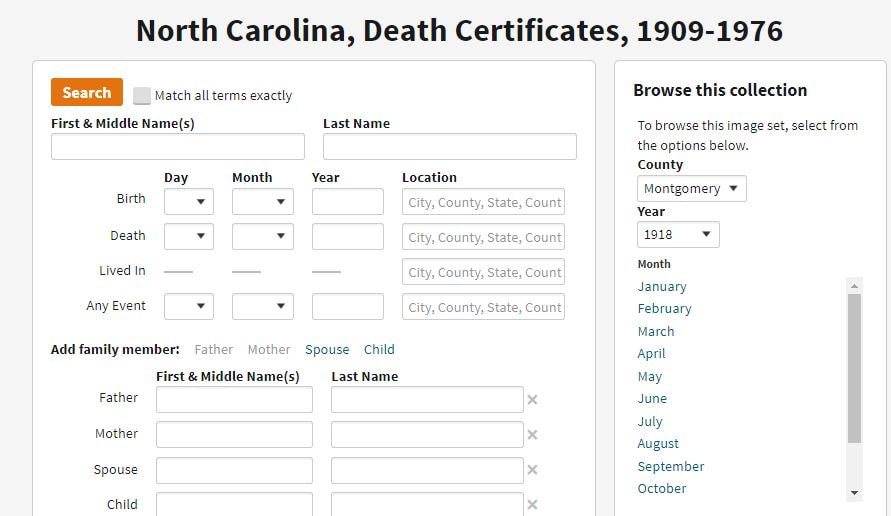

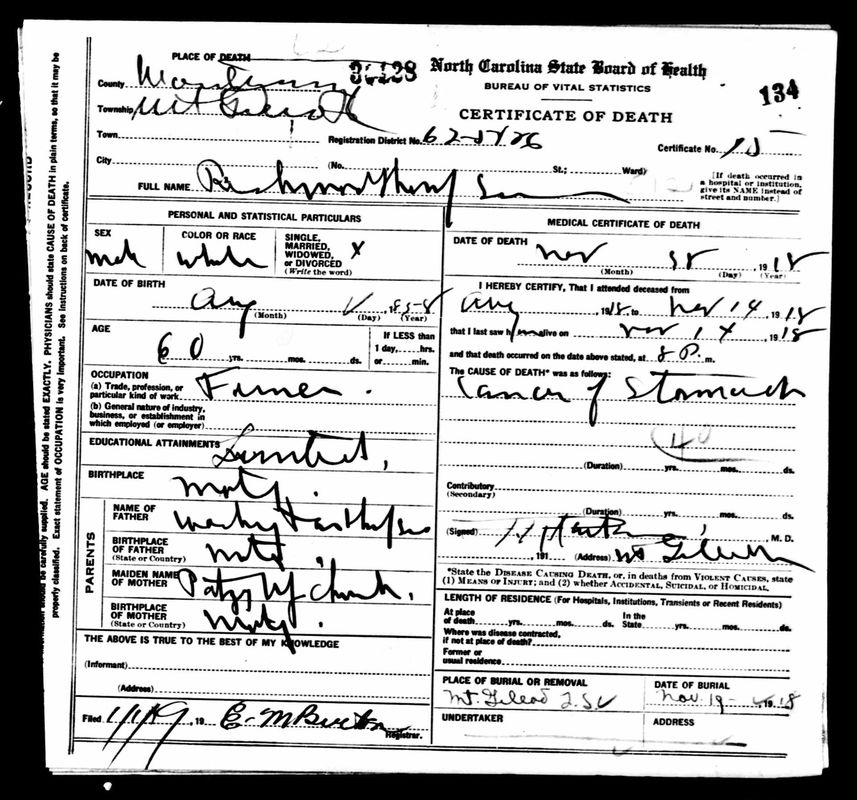

Not all records are indexed!! Like many other people, I use Ancestry's little green "leaf" hints to direct me to records about the subjects I'm researching. Unlike many others, I evaluate those hints critically in order to make my own decisions on whether they're correct. I also look for records that should be in the list of hints, but aren't. A case in point is Richmond Patrick Thompson, who was born in Montgomery County, North Carolina in 1856, and died there in November 1918, according to his memorial page on Find A Grave: Find A Grave (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi/), memorial 91459021, digital image on 14 June 2012 by Brenda King of Richmond Patrick Thompson gravestone (Stoney Fork Baptist Church Cemetery, Mount Gilead, NC). On the Ancestry family tree I've created, the profile page for Richmond Patrick Thompson has a total of 9 hints listed: It's very easy to look at the list of hints that are there. What is not so easy is looking for what's NOT there. In this case, a North Carolina Death certificate. Ancestry's collection of digitized NC death certificates begin in 1909, so Richmond Thompson's death certificate should be there. However, for some reason, it either has not been indexed, or was indexed incorrectly. Just to be clear, Richmond Thompson is listed on the North Carolina Death Index: The source citation for this record would be: "North Carolina Death Indexes, 1908-2004," Ancestry > Wilson > 1914 > T > image 13 of 18, entry for Richmond Thompson (1918). However, there are a couple of problems with this. Richmond Patrick Thompson died in Montgomery County in 1918, not Wilson County.in 1914. I looked at another 1918 death record on this same page (for Roland F. Thompson, who died in November 1918), it was from Duplin County. So this index page is for several counties, and several years, not just Wilson County in 1914. When I decided to browse this collection, I found something totally different: This appears to be a hand-written register for Montgomery County, and according to Ancestry's source information, was created by the North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics. Richmond Thompson is not listed. I still want to see a death certificate, because it is the original record. Indexes like these, even if they are hand-written, are derivative records created from original records. My next step is to browse Ancestry's collection of North Carolina death certificates, zeroing in on Montgomery County in November 1918: And sure enough, I found it. At first glance, the reason it wasn't indexed is obvious: the record is almost entirely illegible. The citation for this record is: "North Carolina Death Certificates, 1909-1976," Ancestry > Montgomery > 1918 > November > image 13 of 14, death certificate 134 (1918), Richmond Thompson.

There are several reasons why I concluded this is Richmond Thompson's death certificate:

Conclusion: Be active, and not passive, in your search for your ancestors. Don't just look for the records that are there, but look for the records that aren't there, but should be. This goes for other types of records, too - census, military, immigration - not just vital records. Browsing an indexed collection could reveal the record you need! Sermon preached at St. John's Episcopal Church, 7 October 2018.

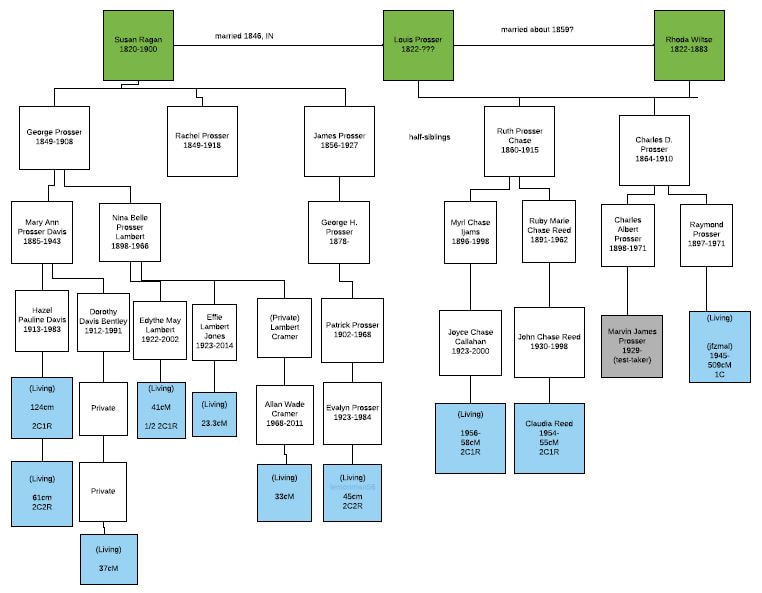

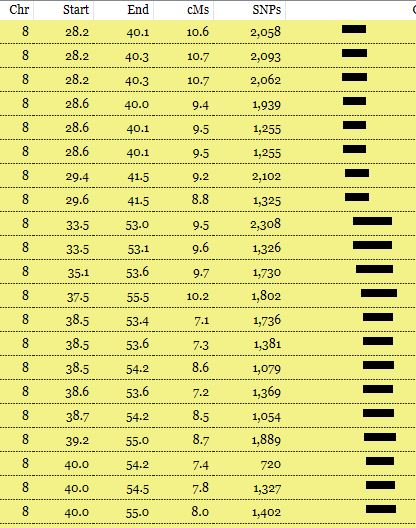

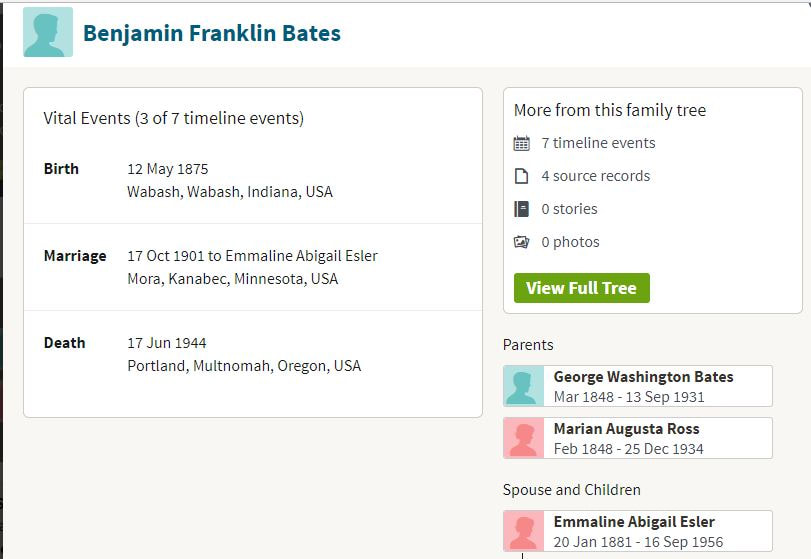

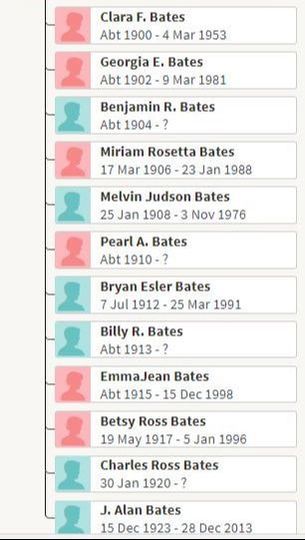

The Lectionary Readings can be found here. (Track 2) So, imagine this: you get up one morning, go to your computer and you see that your Ancestry DNA results are in. You start looking at your matches and realize that the man you thought was your father all these years, wasn't really your father. Imagine that your mother was very proud of being full blooded Cherokee and Choctaw, but your DNA test shows zero Native American ancestry. Imagine that you’re an adoptee, and when the state of Washington opens original birth certificates, you send for yours and you discover that your birth mother was only 14 when she got pregnant. These are issues I deal with every day in my work as a professional genealogist. Since I first began researching over 40 years ago, I have sought the truth for my own family and for my clients. People come to me for information about their origins and ancestry, in seeking an unknown birth parent, or verifying long-told family stories of Native American ancestry or famous Mayflower passengers. In my work, I help people discover the truth of who they really are. Most of us discover who we are within our families, who know us and love us. As Adam clung to his wife, someone he could know and be known by, we are known first within our families, those we grew up with, who truly know and love us. But what happens when there is a disconnect? In today’s Gospel, Jesus recognizes that in answering the Pharisees’ question about divorce. Jesus addresses our brokenness and imperfections, recognizing that Moses allowed for our failures by permitting divorce, but Jesus pointed out that the goal of marriage was to become one flesh: to know and be known. Our deepest longing is for intimacy: to know and be known. We may have a deep longing to know our origins: where we got the shape of our eyes or the color of our hair, where we got our musical talent or writing abilities, or what our ancestors’ lives were like when they decided to cross the ocean to come to America. This longing drives a lot of genealogical research. This longing for intimacy also drives our search for God and being known in this community of faith here at St. John’s. Getting to know the newcomers who walk through our doors and loving them for who they are is always on my mind as a vestry member and head of our Welcome and Inclusion Team. Jesus said, “Because of your hardness of heart he wrote this commandment for you.” He could just as well have said, “Because of your hardness of heart you married three times without divorcing, committing bigamy.” “Because of your hardness of heart you kept your child’s birth father a secret from her….” “Because of your hardness of heart, you shunned the woman who was pregnant with an illegitimate child, while letting the father escape without penalty…” Now DNA testing is telling the truth: shedding a bright beam of light into dark corners and locked closets. DNA results are revealing children born out of wedlock, as the result of an affair, and the parents of babies who were abandoned at the church steps. Just this year DNA databases have been used by law enforcement officers to arrest the perpetrators of violent crimes like rape and murder: both cold cases over 20 years old (including two here in the state of Washington), and current cases that happened just months ago. There are private support groups for the children of artificial insemination, for adoptees seeking their birth parents, and for those who have received the devastating news that they were born as the result of incest within a family. Children can have an intuitive sense when they don’t fit in within a family, and as adults that sense is often verified when an adoption or previously unknown half-sibling is revealed. DNA testing can discover that long sought-for unknown parent or grandparent. DNA testing can confirm or refute long-held assumptions about ethnicity or origin. DNA testing can save lives, uncovering the inherited gene that causes breast cancer. An article in the Boston Globe two months ago titled “The Twilight of Closed Adoptions” stated “For most of the last century in the United States, adoption was shrouded in secrecy and anonymity. For adoptees to find birth relatives took considerable effort, if it was possible at all.”[1] And I could add to that, that the women who felt the stigma, shame and secrecy of giving up illegitimate children for adoption, even as late as the 1970s, still feel that shame today. I’m working with one of them. Renowned genetic genealogist CeCe Moore stated at a recent conference in Arlington, Washington that “because of DNA testing, families are being reunited and identities reexamined. Guilt and secrets are heavy burdens, and for the most part, the truth revealed in our DNA is leading to healing and hope. Because of the popularity of DNA databases, justice is being done and society is safer as a result.”[2] Jesus said, “Let the little children come unto me…” I’d like to tell you the story of one such child, a story of redemption. When we moved to Gig Harbor almost 5 years ago, I came to St. John’s knowing no one. Over the course of a few weeks I made a few friends on Facebook, to get to know more people in the area. One of those was a woman named Rebecca. One day I saw her here on Sunday morning, and we pointed to each other and said, “Facebook!” A few weeks later I messaged her, and offered to trace her family tree, because that’s what I do. Her response was immediate and adamant – she wanted nothing to do with her birth family; it was her foster family that she clung to. I didn’t necessarily understand her perspective, but I did respect it. As I got to know her better, I began to understand. Her birth mother had schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and when a concerned neighbor noticed that 12-year old Rebecca had been living in an abandoned house without water, plumbing or food for over a week, the authorities were notified, and Rebecca and her younger siblings were placed into foster care. But I kept seeing her post on Facebook, musings about how since she didn’t know who her birth father was, how could she tell if she might be dating a sibling. And I kept telling her: “DNA will give you the answer!” Last summer I made her an offer she couldn’t refuse: Ancestry DNA tests were on sale, and if she would buy the test, I would do the analysis and communicate with her matches, for as long as it took, for free. When her results came in, it wasn’t long at all before I could tell her, “Your great-grandparents on your father’s side were Benjamin Bates and Emeline Esler; they were from Minneapolis, and came to Portland, Oregon by 1940.” The only problem was that they had twelve children, at least 20 grandchildren, and who knows how many great-grandchildren; in order to find Rebecca’s birth father, I would have to trace all of these descendants to the present, to find a candidate who was living in the Portland area in the right time frame. Although I did reach out to a potential second cousin match who responded to my email, the conversation stalled. Then in January of this year, I got an email from a first cousin match named Kari, who was really interested and enthusiastic about helping Rebecca. Because Rebecca was so concerned about her privacy, I acted as a go-between. As Kari and I emailed back and forth, she consulted with her family and told me that the consensus was that Frederick Gordon Granberg was Rebecca’s birth father. Although he died in 2012 Rebecca had an older half-brother, Harold Granberg. It turned out that her birth father’s family knew about her, but only knew her first name; they didn’t know her age or where she lived. Rebecca drove down to Oregon soon afterwards to meet her new-found family and walked into a room full of people with their arms open wide, welcoming her into a circle of light and love and warmth such as she has never known before. Now Harold comes up from Portland to work on his little sister’s car, and Rebecca calls him “Brotherface.” They look so much alike they could be twins. Obviously, not all reunion stories end this joyously. I’ve done research for other clients to find an unknown parent or grandparent, only to be met with silence from new-found cousins. And any kind of record, not just DNA, can lead to unsettling news – a dishonorable discharge from the army, criminal activity, illegitimacy, murder and suicide. When we research our ancestors, we must take the bad with the good. When it comes right down to it, though, it makes no difference who my great grandparents were. Does knowing that my 2nd great grandfather was probably a bigamist, deserting his regiment during the Civil war, or knowing that my great-grandfather Henry Chase died in an insane asylum make me any less of a person? Does that fact that my husband’s mother was not actually Cherokee and Choctaw, as she thought all her life, make him any different? That’s a resounding no – because no matter who our ancestors were or what they did, and no matter what DNA testing reveals about me, my origins or my ancestors, I know with every fiber of my being that I am known and loved and cherished by God, and an integral part of His kingdom here on earth and in his kingdom that will have no end. Amen. [1] S.I. Rosenbaum, “The Twilight of Closed Adoptions,” Boston Globe, 4 August 2018, (https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2018/08/04/the-twilight-closed-adoptions/1Iu4c5da4W5qNbIPn5IEmL/story.html: accessed 30 August 2018). [2] CeCe Moore, “Making History with Genetic Genealogy,” Northwest Genealogy Conference, Arlington, Washington, 17 August 2018. I first started learning about DNA and its uses in genealogical research many years ago. My first DNA test was with 23andme, when they offered a test for the low price of $14.95 plus a year subscription to updates, at $9 per month. My matches were interesting, but not that useful. The only match I recognized was a cousin I'd already been corresponding with, who was a descendant of my German great-grandmother Caroline Dorsch Stoelt. I was very slow to test in other companies because DNA testing was expensive and I didn't understand how to use it.Yet. In 2014, when the very first institute on Practical Genetic Genealogy was offered at the Genealogical Research Institute of Pittsburgh, I managed to get into the 2nd class (opened because the 1st class filled in a matter of seconds). I learned a tremendous amount in that class, which was taught by Debbie Parker Wayne, Blaine Bettinger and CeCe Moore, but I found that every afternoon about 2:30 pm my brain shut off and informed me that it Could Not Take Any More Information. Since then, I have watched every DNA webinar offered by Legacy Family Tree Webinars, especially those offered by Blaine Bettinger. Through Feedly, I subscribe to every blog post written by Blaine Bettinger, Debbie Parker Wayne, CeCe Moore, Kitty Cooper, Roberta Estes, and many others.I've also watched webinars on DNA offered by the Association of Professional Genealogists, the Board for Certification of Genealogists, and the Virtual Institute of Genealogy. For the past two years, I have ordered and watched the entire set of videos from the International Institute for Genetic Genealogy annual conference, held in San Diego, CA in 2016 and 2017. All along, I have practiced what I've learned. In 2012 I finally did a Family Finder test at FamilyTreeDNA, and last (but not least) did an Ancestry DNA test a couple of years later. As I could afford it, I tested other family members: my brother Craig Reed did a Y-12 test at FamilyTreeDNA before he died in 2014 (note: I need to upgrade that....); my husband Richard did the Y-37 test, and then the Ancestry test (which held a huge ethnicity surprise); my nephew Jason Reed did the Y DNA test at Ancestry before it was discontinued (which I transferred to FTDNA and upgraded to Y-37), and my son-in-law Perry did the Y-37 test at FTDNA, which revealed his Sage ancestors. The test which (for me) was worth its weight in gold was the Y-37 test my cousin Marvin Prosser took at my request, which proved that we are descendants of John Prosser of Rhode Island. A couple of years later, in 2015, he took the Ancestry DNA test, which led to the discovery of our Wiltse ancestors, and last December, to the Prosser DNA matches proving our link to Louis/Lewis Prosser of LaPorte County, Indiana. About the same time I broke through my 43-year brick wall, I solved my first unknown parentage case. Since the beginning of this year, I've solved or come close to solving six unknown parent or unknown grandparent cases, in two of which the father or grandfather changed his name. At this point, I needed more education, and lots of it. I needed something beyond the basics, namely how to use chromosome browsers and segment data, to help me work with clients and my own research. It took me about ten seconds to sign up for Blaine Bettinger's new endeavor, DNA-Central. I began reading and watching the courses there, and as always, no matter how much I thought I knew, I always learn something more. I've been learning how to use DNAPainter, and just today began the tutorials on how to use GenomeMate Pro. One of the tools I have learned how to use is LucidChart. Here is a chart I made that displays convincing evidence that Louis Prosser was my 2nd great-grandfather and the father of my great-grandmother Ruth Prosser Chase: Thanks to Dr. Leah Larkin's tutorials on GenomeMate Pro, I have been learning how to use this tool for advanced analysis. Here are some of my matches from GedMatch, showing the chromosome segments where they match me on chromosome 8: With everything I learn, I feel more empowered to make significant progress in my own research and my work with clients, especially those with unknown parents or grandparents. I now have 3 mantras that I believe to be true: There is always something more to find.

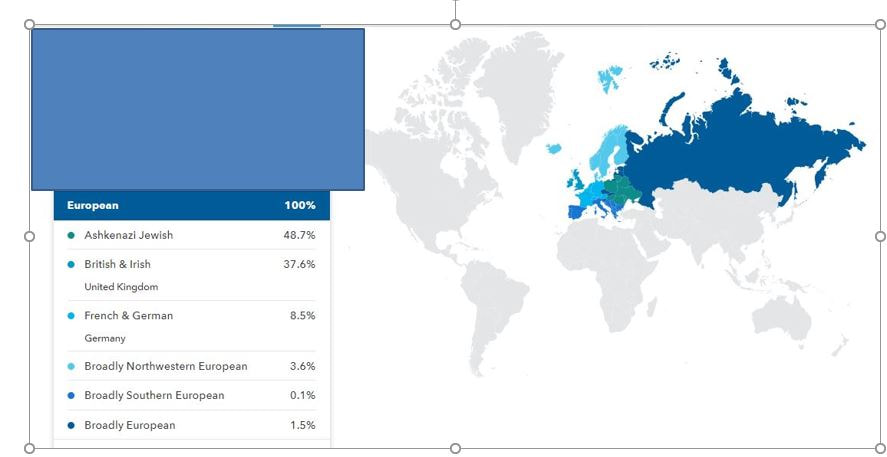

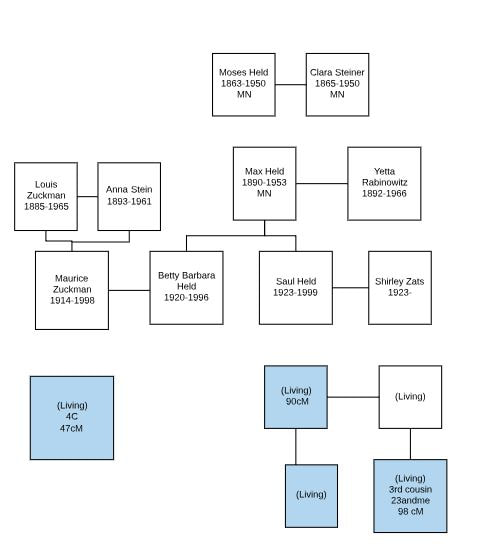

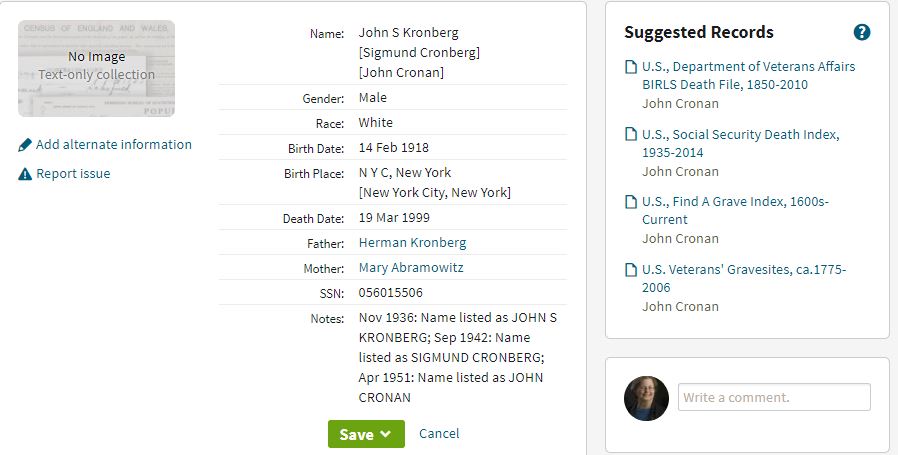

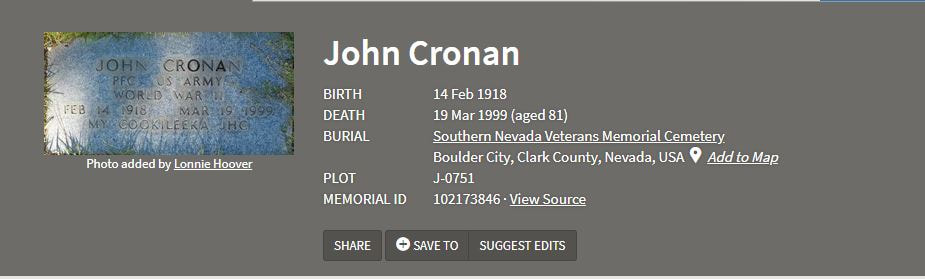

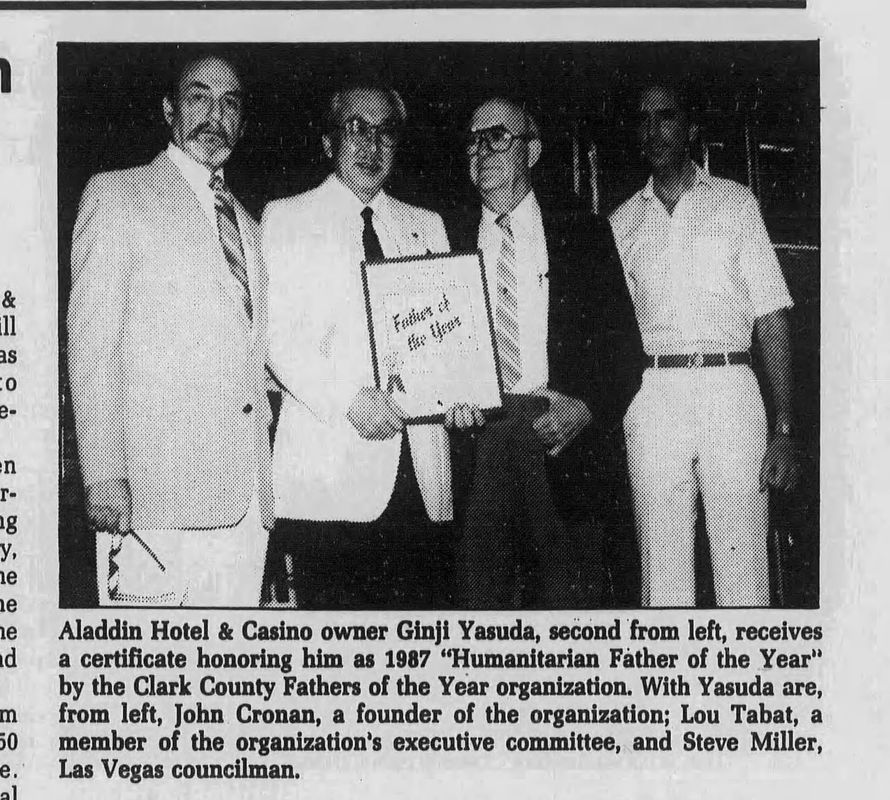

There is always something more to learn. And There has never been a better time to be a genealogist! Several years ago my client Lisa decided to do a DNA test with 23andme. Much to her surprise, she turned out to be 49% Ashkenazi Jewish. She said in her initial email: "What a surprise from a girl who grew up thinking she was Norwegian, Irish, English, German, French and of course, some Native American in there somewhere!" Out of curiosity Lisa's sister took the test - and they turned out to be half sisters, with the same mother but different fathers. When Lisa confronted her mother with the results, she admitted having a brief affair with a man in the entertainment business in California about that time, who had changed his name to John Cronin. He was originally from New York, and also 20 years older than she was. With that, her mother let it be made known, The Subject Was Closed. Lisa had already done a great deal of the work - in addition to 23andme, she also tested with FamilyTreeDNA and Ancestry, and uploaded her raw data to Gedmatch. But that's where her knowledge ran out, and I came into the picture - admittedly, because she was excited to find someone living in the same area. So was I - it's not often I get to meet my clients! I first took a look at Lisa's 23andme results. Her ethnicity report was right on the money: Her Ancestry DNA ethnicity report was very similar. But (of course) I was mostly interested in her matches. Very helpfully, since Lisa's mother and sister had tested at 23andme; many of her matches there were identified as "Mother's Side". I zeroed in on the rest. Her top paternal match was a man at the 2nd-3rd cousin level. From some judicious sleuthing, I found that he was a businessman living in Jerusalem. I contacted a colleague of mine in Israel, who supplied me with the man's phone number, and first names of his parents. Not much help there. Using the "in common with" tool, I found 3 other matches who were (after some Facebook searching) probably a father, with his daughter and son. Using a variety of resources, I found that they were descendants of Saul Held, 1923-1999, who lived in Minneapolis. (Tip: Newspapers.com has an excellent collection of Minneapolis newspapers!) Lisa had another 4th cousin match who was a descendant of Maurice Zuckman, 1914-1998, who also lived in Minneapolis. It didn't take me long to find that these two families were connected. I used LucidChart (and Lisa's Ancestry family tree, which was private and unsearchable) to keep track of the relationships: It was nice to tell Lisa that her paternal ancestors probably included Moses Held and Clara Steiner, but that got us no closer to her father's name. After hours of working with newspapers, Facebook, online directories, Ancestry, and other resources, I had gotten no farther. With Lisa's blessing, I decided to take a break to concentrate on other client projects. Sometimes the key word is "patience". At the moment I keep track of 35 Ancestry DNA kits, and almost that many at FamilyTreeDNA. I'm not actively researching all of them, but it's nice to have them on hand to look at whenever I learn something new. About a week ago, as I was watching (yet another) webinar on DNA, it occurred to me to check Lisa's Ancestry results again. And how about that - she had a predicted 1st-2nd cousin match, who did not match a known cousin on her mother's side. His name was Joseph. I found him immediately on Facebook, with a friends list a mile long, at least half of whom had Jewish names: Levine, Cohen, Feinstein, Rosenbaum, Kaufman, Moskowitz. His wife's maiden name was Jewish. After doing research in online newspapers, I found his paternal grandmother's obituary. There was only one problem. She was Catholic. There it was in black and white: "Funeral services will be held at 9:15 a.m. Sunday from the funeral home, followed by a 10 a.m. Mass at St. Stanislaus R.C. Church....." In disbelief, I returned to Facebook and double-checked. By looking at several friends' pages and doing more online searching, I deduced Joseph's mother's name. From there I soon found an article about her parents' 50th wedding anniversary, and both their obituaries. They were Jewish, with the last name of Kronberg, which I thought was close enough to Cronin to start getting cautiously excited. (If there is such a thing!) It didn't take long (with 20 tabs open on my browser) for me to find an obituary for the matriarch, Mary Kronberg, which mentioned the children and grandchildren I already knew about, plus one other son: John. When I searched on Ancestry, in the U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, there he was: In the suggested hints was a link to Find A Grave, where I found his gravestone: Lisa, of course, was elated, and philosophical when I told her that her father was deceased. From start to finish, this project took just a little less than two months to solve.

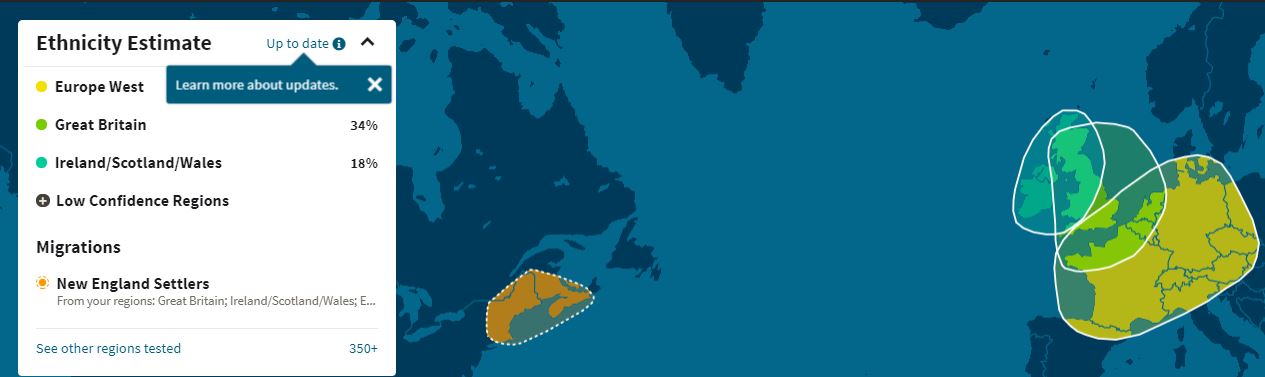

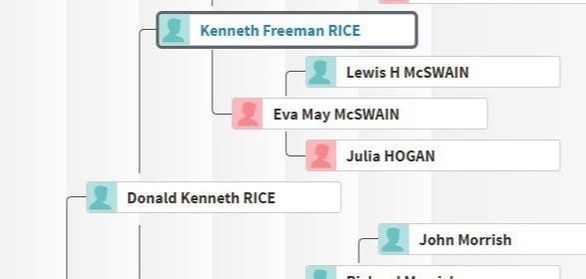

Of course, genealogy is never really finished..... A key piece we are still missing is the maiden name (and parents' names) of the wife in the 50 year anniversary announcement. I have her Florida obituary, and I've sent for her death record. Another key piece is that Mary (Abramowitz) Kronberg had a Social Security number, and so I've sent for a copy of her original Social Security application. I'm hoping that these ancestors will tie in to her other matches, so that I can map out a (more or less) complete family tree. Perhaps the greatest gift I gave Lisa is a newspaper photograph of her father: (some names in this story have been changed) Earlier this year, I was contacted by a man who wanted to find his birth father. Frank had heard from his birth mother that his father's name was Matthew, and that he had Polish ancestry. He had done the Y-37 test at FamilyTreeDNA, and on my advice, took the Ancestry DNA test as well. His Y-37 results were confusing to him, because most of the matches had the surname Rice, which was his maternal grandmother's maiden name. Out of 33 matches, 24 of them were to men with the last name of Rice. Seven of these men traced their ancestry back to Deacon Edmund Rice, who died in Massachusetts in 1663. His Ancestry DNA results were also very interesting. I don't usually pay much attention to ethnicity estimates, but in his case I looked at them, looking for Eastern Europe ancestry. It wasn't there. I also noticed the New England Settlers migration pattern. Frank's top match on Ancestry was a first cousin, whose father, Donald Rice, died in Denver, Colorado in 1974. (Frank was born in Denver in 1980.) I emailed this first cousin match, without a response. In my written report I made these points:

Two weeks after I sent the report, I got an email from Frank's first cousin match, who wrote:

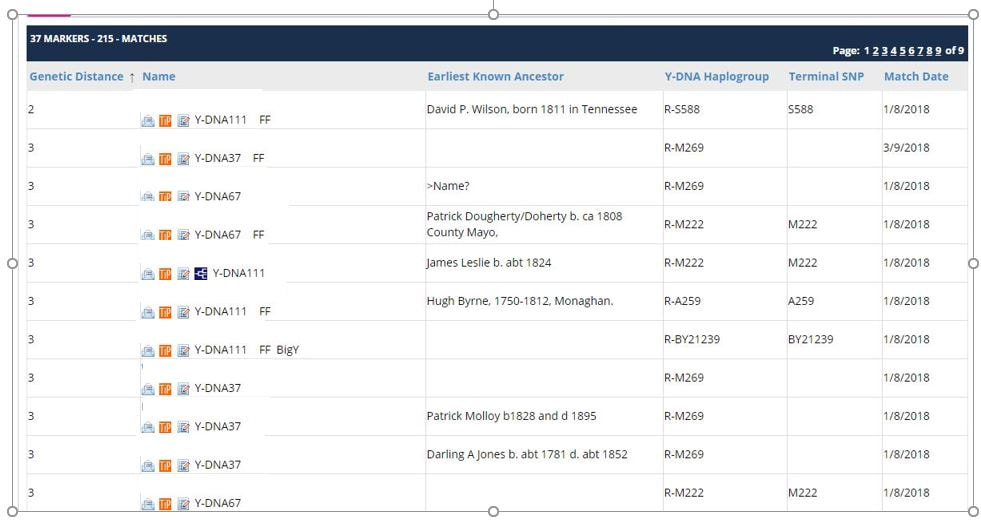

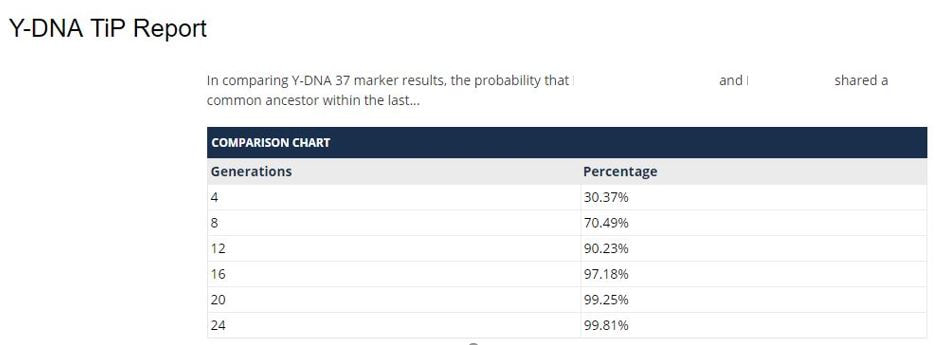

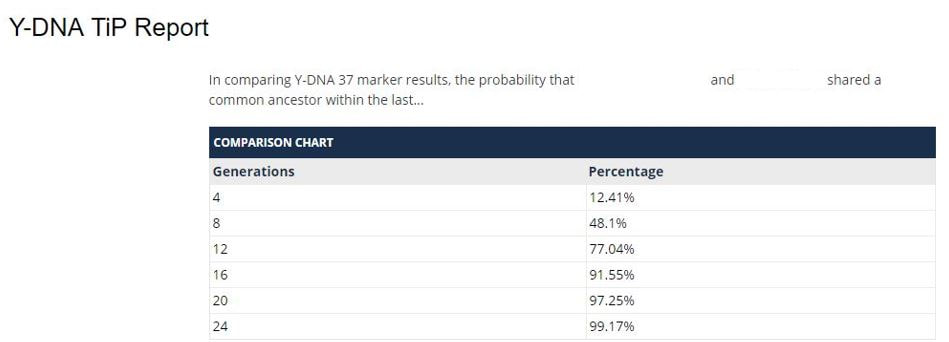

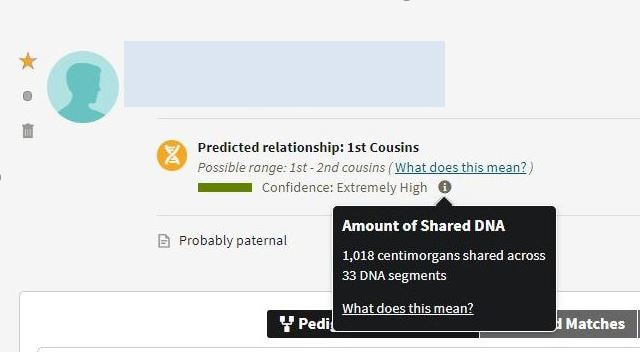

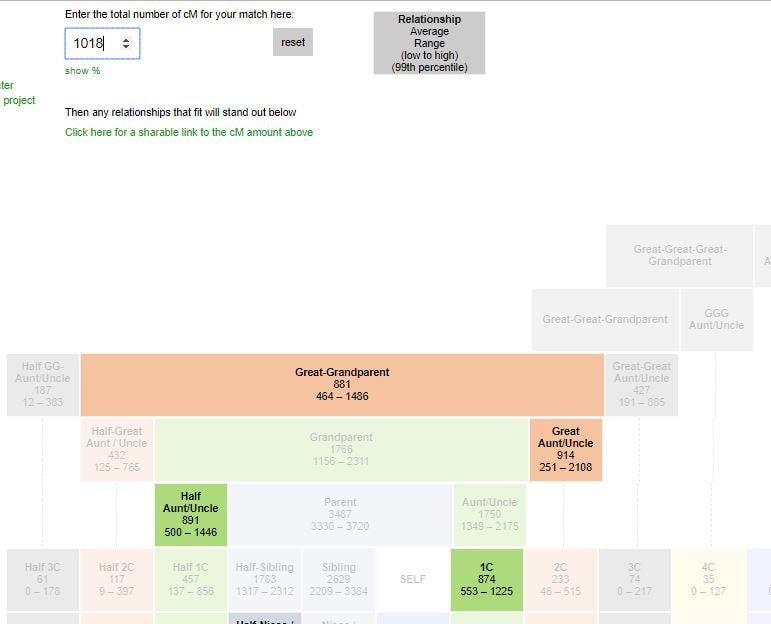

My dad Donald Rice and his first wife Sheila had 2 kids, Matthew & Sylvia. Sheila remarried at some point and her new husband adopted Matthew and Sylvia, and their names were changed from Rice to their stepfather's name. Unfortunately, Matthew died in 2016. In spite of that, Frank's new-found family welcomed him with photos and memories, and a planned reunion. (All names and locations have been changed.) Several years ago, when original birth certificates were made available to adoptees in his state, Sam learned the identity of his birth mother. She had been living in a home for unwed mothers in the early 1970s, and was barely 15 years old when he was born. Last year he found her (since married) on Facebook and sent her a message, which went unanswered. Now he wanted to find the identity of his birth father. Sam didn't want to upset anyone or cause trouble; he just wanted to know his name. On my advice, Sam tested with Ancestry DNA and transferred his raw data to FamilyTreeDNA. In addition, he took a Y-37 marker test at FTDNA. Two of Sam's top four matches on FamilyTreeDNA's Family Finder were at the 2nd-4th cousin level, sharing 143 cM and 93 cM; both traced their ancestry back to Patrick O'Malley and his wife Mary, who came from Ireland and settled in Wisconsin. They had several children and at least four of their descendants were on Sam's match list. As for Sam's Y-37 marker results, the surnames of the testers and their farthest paternal ancestors were all over the map: The top two Y-37 matches for Sam had a genetic distance of 2 and 3, respectively. The TIP report for each one of them helped to explain the results: Sam's first match, with a genetic distance of 2, only had a 30% chance of sharing a common ancestor within the last 4 generations. With his second Y-37 match, that percentage went down to 12.41%. With the second match, to find a common ancestor with a greater than 50% chance we’d have to go back 12 generations; well over 250 years. No help there. Sam’s Ancestry DNA results were more promising, but still took a great deal of work. Of his top six matches, at the 1st & 2nd cousin level, four of them had the last name of Michaels and none of them had a family tree. From previous research I knew that only one of these top matches was on his mother’s side; the rest were paternal matches. Of these Michaels matches, three of them had not logged in since last August. The first paternal Michaels match shared 1018 cM; which seemed to indicate a strong first cousin match. I use DNA Painter on a daily basis, and their graph verified my conclusion: The 2nd of his paternal matches was identified only by initials: “C.W.” (administered by Jonathan Wilde). Jonathan Wilde’s profile on Ancestry identified the city and county where he lived. Using an online directory, I found that Jonathan Wilde’s wife was Catherine Wilde, and speculated that it might be her DNA test, instead of his. Going to Facebook for more sleuthing, I easily found her profile, which included her maiden name of Kavanaugh. Interestingly, in her friends list were several friends with the last name of Michaels; who may (or may not) be related to her.

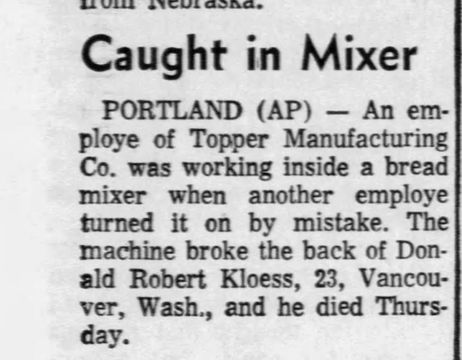

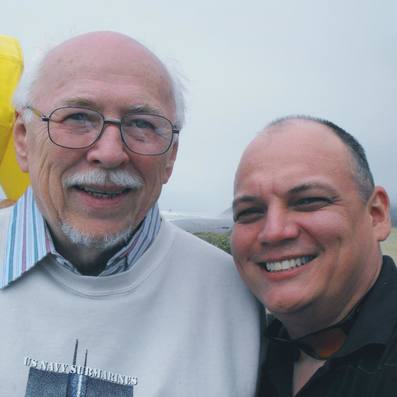

One of those Michaels friends had posted a “miss you dad” on February 23, 2017, with a family picture, obviously taken when his dad was still living. I wondered if February 23 was a significant date; perhaps a family birthday or wedding anniversary. On to research several vital records databases for the state in question, and I found a 2016 death record for a Richard Michaels. I found a full obituary on Legacy; it listed his birth date as February 23, and named his deceased parents, deceased siblings (including Rosemary Kavanaugh), widow and surviving children. Interestingly, his mother was Bridget (O’Malley) Michaels, daughter of the same Patrick O’Malley I’d seen on FamilyTreeDNA. I looked up the obituaries for Richard Michaels’ deceased siblings, and sure enough, Rosemary (Michaels) Kavanaugh had a daughter whose name was Catherine (Kavanaugh) Wilde, possibly one of Sam’s top DNA matches. Richard Michaels and his siblings all lived in the same city where Sam’s birth mother and her parents were living when he was conceived. Since Richard Michaels’ deceased parents were named in his obituary, it was easy to research them and find their children and grandchildren; from that research I could identify two of the Michaels matches to Sam. At this point I began to suspect Richard Michaels who died in 2016 of being Sam's birth father. He had been married three times, with children from each marriage. Richard was ten years older than Sam’s birth mother and had married and had his first child the year before Sam was born. I began to have a not-so-good feeling about this. At the age of fourteen, any pregnancy was the result of statutory rape, whether consensual or not. I began to wonder if Sam’s birth mother had been the family babysitter. At some point in this research, Sam’s adoptive mother emailed me, saying that she was thinking about writing a letter to Sam’s birth mother. I replied immediately, saying “NO! Full stop. Sam is the adoptee here, and that’s his job. I would be glad to look over the letter before you send it to Sam, but in the end, it’s his decision whether to contact or not.” When I was sure about Sam’s birth father being a Michaels, I sent an email to the Wildes through Ancestry’s DNA messaging system: "I'm working with an adoptee who was born in ________; his birth mother was from _______. This adoptee is a 1st cousin match to you, along with ________, ________, ________ and ________. From other matches on FamilyTreeDNA, I've determined that he is most likely a grandchild of Bridget (O'Malley) Michaels..He is not seeking a relationship, just further knowledge of his ancestry." There has been no response, even though they have checked their Ancestry DNA several times a month since then. This story does not have an ending. The paternal cousins have not responded, and I don’t expect them to. Sam is content knowing his ancestry; he’s Irish on both sides of his family. And while genealogists are by nature curious (what was the story?), curiosity is no reason to wake up sleeping dogs. Genetic genealogists must act in an ethical manner, and that means respecting the wishes and emotions of the living, who may be deeply impacted by the result of an unexpected DNA match. The National Genealogical Society's Guidelines for Sharing Information with Others states: "Genealogists and family historians are sensitive to the hurt that information discovered or conclusions reached in the course of genealogical research may bring to other persons and consider that in deciding whether to share or publish such information and conclusions." (Emphasis mine.) So - research stops, and the deceased birth father's family are allowed to live in peace. I first got to know Rebecca at my church about four years ago. Since then, I’ve been impressed by her resilience in the face of abuse, neglect, and serious illness and tragedy. She was deeply involved in Toastmasters, winning many awards for her speeches and evaluations, and was involved in softball as well. Like me, she ran her own business, doing photography and marketing for local shops in Gig Harbor, Washington. I learned early on that her mother had multiple personality disorder, paranoid schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, regularly abusing, starving, and otherwise neglecting Rebecca and her other children; once leaving Rebecca (then age 14) in a condemned house with no electricity, running water, or food for over a week. Upon the report of abuse and neglect by a concerned neighbor, Oregon State took custody of Rebecca and her two younger siblings and put them into foster care; they were unsuccessful in finding Rebecca’s birth father. The problem was that the man named as the father on Rebecca’s birth certificate, Donald Kloess, died in 1967, nine years before she was born. "Caught in Mixer," Statesman Journal Salem, OR, 11 February 1967, p.10, col. 1. Whenever I heard Rebecca wonder aloud about her birth father, or muse on the likelihood that she’d end up unknowingly dating a sibling, I reminded her that her DNA held the answer. Finally, during an Ancestry sale last summer, I made her an offer she couldn’t refuse – if she would buy the kit, I would do the DNA analysis, no charge. Rebecca's DNA test, 16 July 2017; used with permission. Our next step was both easy and hard – we waited. While we were waiting for the results, I created a private, unsearchable tree for Rebecca, who was almost paranoid about her privacy. On Facebook she used a pseudonym, not wanting any contact with her birth mother. Fortunately, she was on good terms with her aunt on her mother’s side and had a file folder full of information on her maternal side of the family. I was saddened but somehow not surprised to read about and research the history of mental illness, suicide, and abuse on her biological mother’s side of her family. When the results came in, it was easy to separate Rebecca’s paternal matches, as her aunt had already tested with Ancestry. It wasn’t long before I was able to send a preliminary message to Rebecca, that her paternal great-grandparents were probably Benjamin Bates and Emmeline Esler. This couple had met and married in Minnesota, and were in Multnomah County, Oregon by 1940. As I had time, I would add information to Rebecca’s tree, tracing all the descendants of Ben and Emmeline’s 12 children. Most of them stayed in the Portland area, which made things a little harder. I would need to follow each of their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren to the present in order to find a possible candidate for Rebecca's birth father. Then in August, I sent a cautiously worded email to a 1st/2nd cousin match, not revealing the age or gender of the adoptee: Hello - I am a professional genealogist, working with an adoptee who has unknown parents. You show up as a 1st-2nd cousin match; from my client's other matches I'm seeing close matches to the family and descendants of Benjamin Bates and Emeline Esler. My client was born in the Portland, OR/Vancouver, WA area between 1965 and 1980. At this point, they are interested in family history; making contact is not a goal. Although this cousin responded to my email, the conversation stalled in November. Then on January 5, I got a positively perky email from a new 1st cousin match: Hello! My name is Kari Hill. I recently took the Ancestry DNA test and found out that someone named R.K. is likely to be my first cousin. I would love to know more and would appreciate any information that you can give me. Thank you! Kari Kari and I were soon corresponding by email, as she answered my questions and I relayed them to Rebecca. Rebecca said I could tell Kari her name, birth date and where she lived. On January 5, Kari emailed me: My mom’s name is Betsy Ross Granberg. Daughter of Betsy Ross Granberg. Unfortunately, three of her brothers have passed away. Benjamin Granberg, Fredrick Gordon Granberg, and just recently Harold Granberg. I still have a surviving uncle Arthur Granberg, but I highly doubt he would be her father. If I had to guess, I would say Frederick (Gord). I hope that helps! Please let me know if I can help in any way. Kari Less than 4 hours later, Kari emailed again: Hello! Yes, my Uncle Gord was married to Beverly Curtice and had a son named Harold Lee Granberg. After asking around we are very sure that My Uncle Gord was the father…. I would like to meet her if she’s up for it. Thanks! I relayed the messages to Rebecca, and her reply was one word: Gordon. I asked if that was a familiar name, and she said, “We always thought Gordon was a last name. A private investigator tried to find him when I was in foster care, but he was searching for “Gordon” as a last name.” I think it was just later that same day that Kari and Rebecca connected on Facebook, followed by several other members of her birth father’s family. Although Fredrick Gordon Granberg died in 2012, Rebecca’s older brother Harold welcomed Rebecca to the family, sending her loving emails, texts and photos. Fredrick Gordon Grandberg and his son Harold Lee Granberg, about 2010. Used with permission. As it turns out, Fredrick Gordon Granberg loved photography, art, and public speaking. He loved taking care of others and telling jokes – all traits that Rebecca shares. In early January, Rebecca told her friends on Facebook: Tonight, over my sister’s elk stew and homemade bread, I learned who I am. And though my birth father is no longer living, he would have wanted me; his family wants me, and I have another brother... As a scrappy foster kid who aged out of care believing I was unwanted, I forged ahead but always searched for him. Today, after 41 years of not knowing who I was, I know my name. Rebecca and Harold, 16 January 2018. Used with permission. I had the privilege of meeting Harold one day in January when he had driven up from Oregon to fix Rebecca’s car – just like any older brother might do for his sister. I learned that Harold and some of his father’s family knew about Rebecca long ago. But they didn’t know her last name, or where she lived. Not all adoptee/birth family reunions end this happily – but it was a joy to play a part in this one. I think my biggest contribution was in persuading Rebecca to do a DNA test in the first place, and then in being a shield for her privacy and a go-between with potential paternal matches. Harold Granberg, Claudia Breland and Rebecca, 28 January 2018. Used with permission.

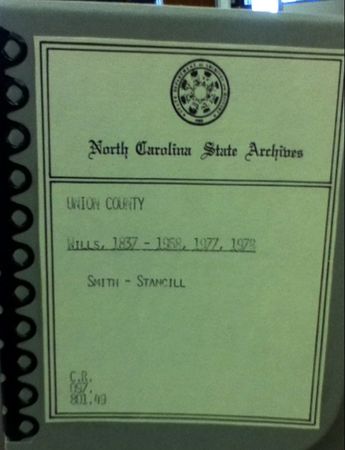

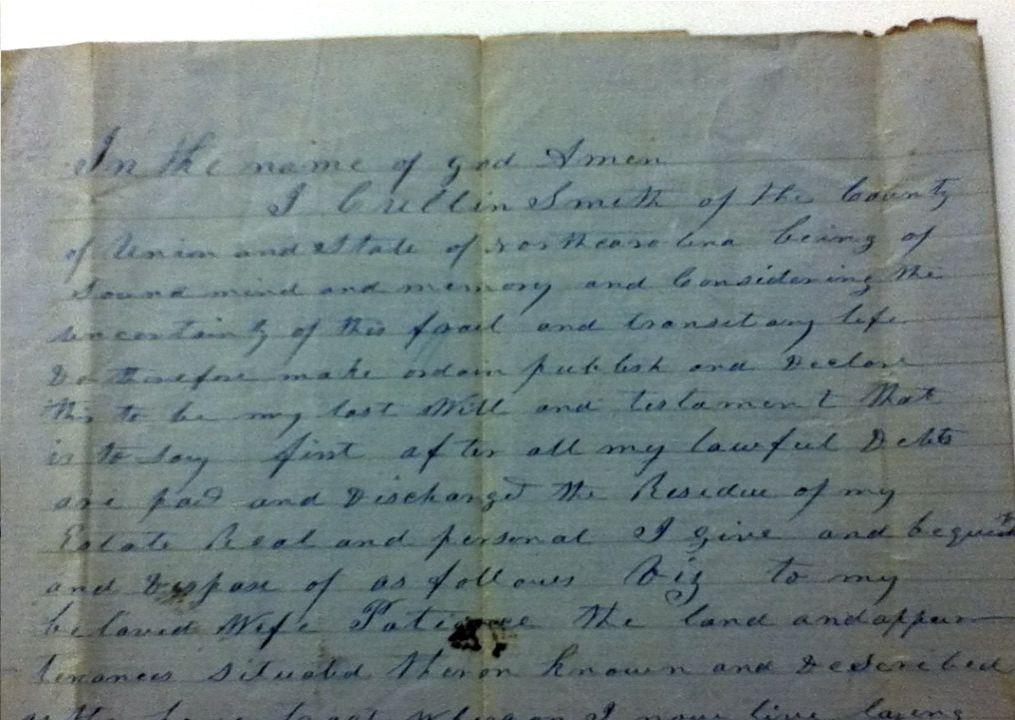

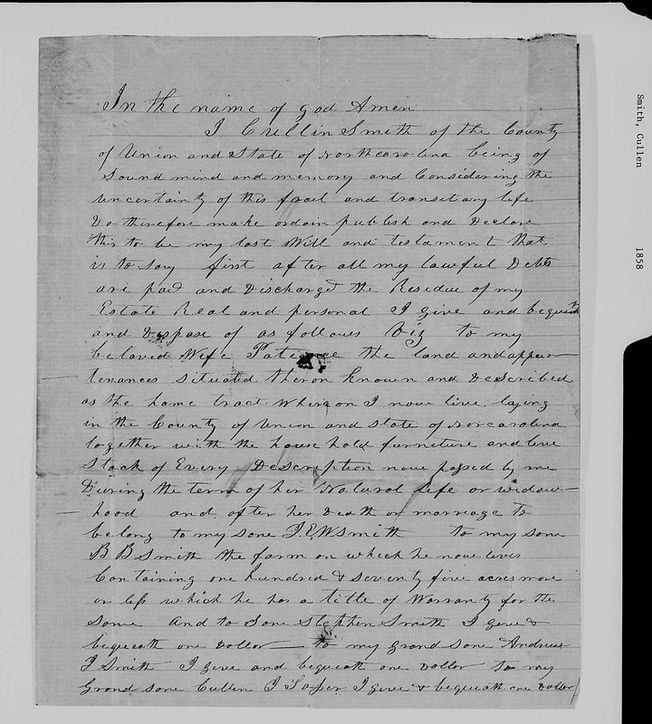

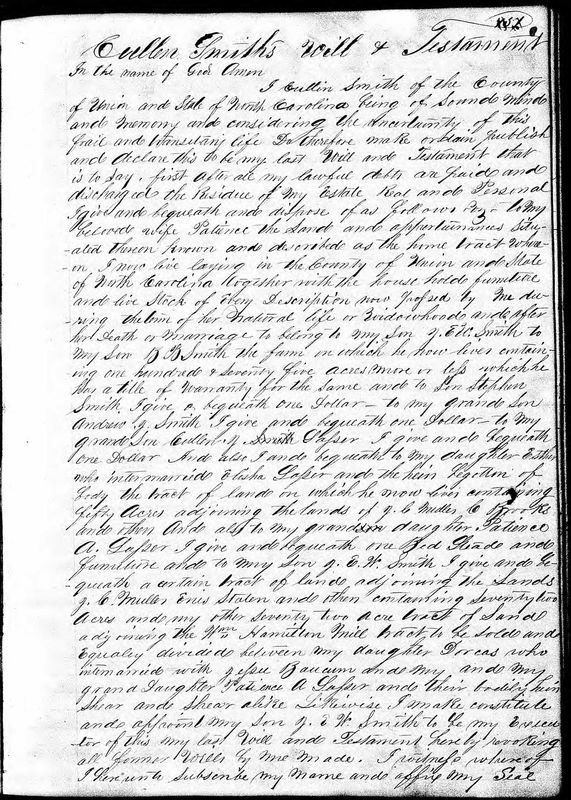

Several years ago, while researching at the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh, I was looking at the original will of Cullen Sasser, which he signed in Union County in February 1858. I was excited to see an original will, as most of the wills I've looked at, online and in person, are written into will books by county clerks. Today, as I was incorporating this will into a family history, it occurred to me that it was probably online by now, at either FamilySearch or Ancestry, or possibly both. So (being curious), I looked it up. Sure enough, on FamilySearch, the original will has been digitized. Citation: FamilySearch (familysearch.org/search/catalog/457255) > Original wills Presson, Eugene P. - Smith, John A. > image 1675 of 1737, Union County, North Carolina, will of Cullen Smith (1858). However, when I looked it up in Ancestry's U.S. Wills and Probates collection, I found a copy of the will that had been recorded by the county clerk in the will book. Citation: "North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998," Ancestry > Union > Wills, Vol. 1, 1843-1868, p.151, will of Cullen Smith (1858). Looking at the two wills side by side, there are some obvious differences that point out the advantages and disadvantages of looking at the original versus a copy:

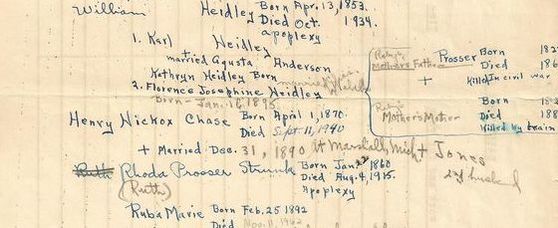

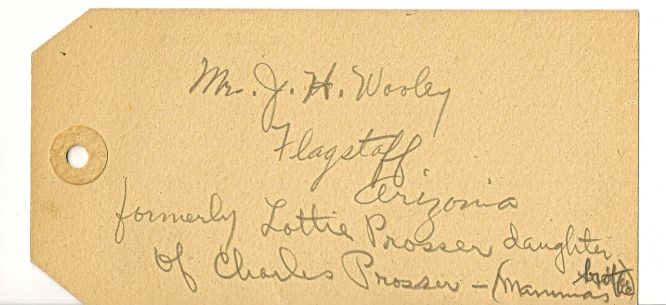

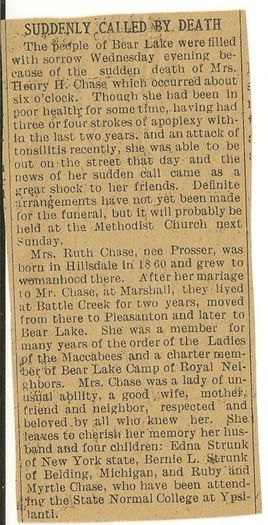

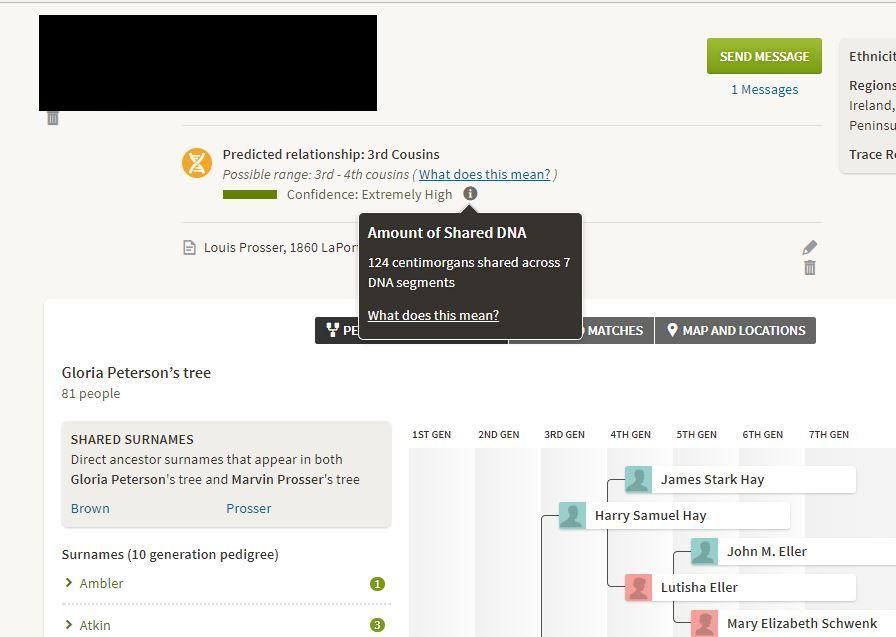

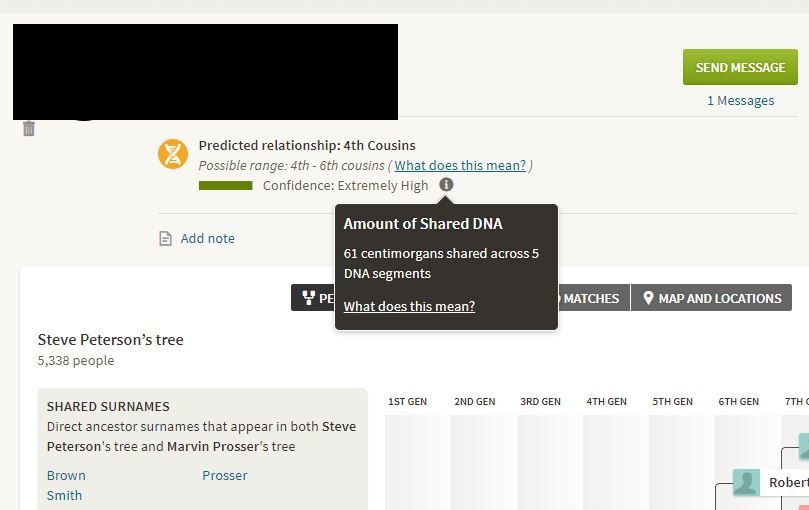

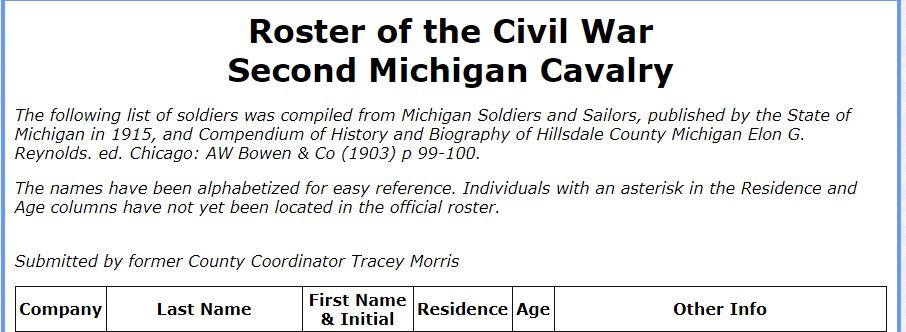

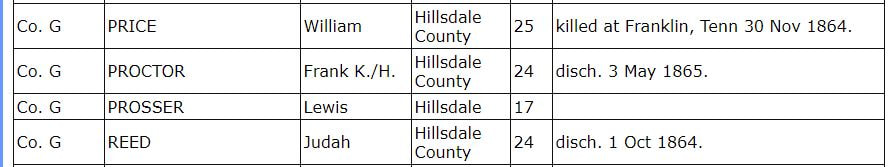

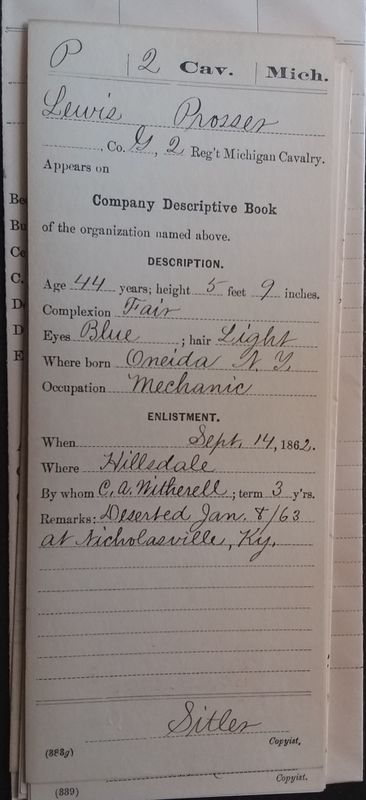

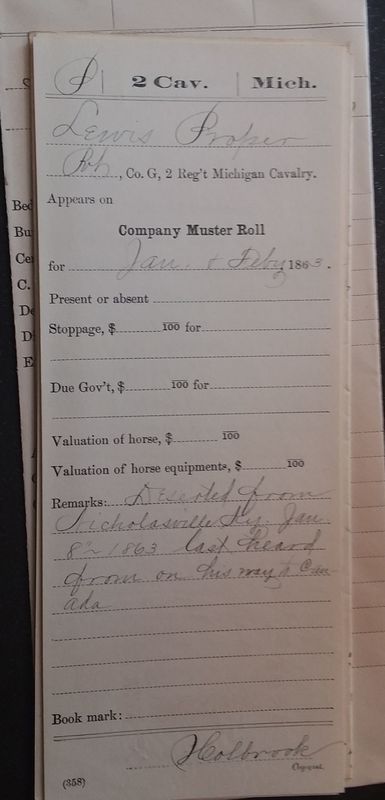

1. The first and most obvious difference is that the clerk made an error in Cullen Smith's grandson's name. Cullen J. Sasser in the original was transcribed as Cullen J. Smith Sasser, with the Smith scratched out. This could lead to some confusion to anyone transcribing the will. 2. The clerk made several changes in capitalization, spacing and punctuation, which may or may not make a difference in the meaning. 3. Cullen Smith mentions his daughter: "And also I and [sic] bequeath to my Daughter Esther who intermarried with Elisha Sasser and the heirs begotten of boddy [sic] the tract of land on which she now lives Containing fifty acres...." The clerk corrected the spelling, but changed the phrase to "on which he now lives." 4. Cullen Smith makes a bequest to his granddaughter Patience A. Sasser; the county clerk wrote grandson, and then lined out "son" and wrote "daughter". Just these differences in a one-page will make it obvious to anyone to recognize when they're reading a copy of a document, and to realize that there may be errors done in the copying. It was over 43 years ago when my father first handed me my Grandpa Reed's files of family history, and I embarked on a lifelong journey. The stories I had heard and the biographies and charts my grandfather had typed went a long way in giving me enough information to get started. He was very methodical in setting down what he knew, but my Grandma Ruby Reed's contribution was a haphazardly drawn family tree: Throughout the next few years I managed to make sense of most of the names, dates and relationships she listed. But there was one man in particular - my 2nd great grandfather (??? Prosser) - who eluded my every attempt to identify him. It's been only in the last 4 years that I've been able to make progress on the Prosser side of my family, and the last brick in the wall was shattered the week after Christmas, 2017. I had two other clues besides Grandma Ruby's chart: a luggage tag (which would prove to be vitally important) and my great-grandmother Ruth Prosser Chase's obituary. I have given up more times than I can count. And more times than I can count, I have looked at Grandma Ruby's chart and wondered, "Mr. Prosser, what was your name? Who were you, and what happened to you?" Now I know at least part of the answer. After finding my cousin Marvin Prosser just a few years ago (he is the grandson of Charles Douglas Prosser, my great-grandmother's brother), his Y-37 DNA test with FamilyTreeDNA proved that we were indeed Prossers. And a couple of years later, his autosomal test with Ancestry proved that my 2nd great grandmother was Rhoda Wiltse, daughter of Reuben Wiltse and Mary Ann Brown. Just a little over two weeks ago, I took another look at Marvin's Ancestry DNA matches. Just for kicks (because I'd done this many times before), I typed in "Prosser" in the search box, to get a list of his matches that had that name on their family tree. And to my surprise, there were several more than the last time I'd looked. Marvin's second closest match was a third cousin, who shared 124cm across 7 DNA segments; the next closest match turned out to be her son, who shared 61cm across 5 DNA segments. They both descended from Louis Prosser, who married Susan Ragan in LaPorte County, Indiana in 1846. Louis and Susan Prosser are listed on the 1850 and 1860 census of Cool Spring, LaPorte County, Indiana. I dismissed him as a possibility - my great grandmother Ruth Prosser was born in Hillsdale, Michigan in 1860 - but other matches, also descendants of Louis, made him impossible to ignore. I took another look at the 1860 census, and noticed something interesting. Although Louis Prosser is listed (occupation: Gold Hustler), Susan was listed as the head of the household, and was listed as a widow. I looked at the map, and LaPorte County was only about 100 miles from Hillsdale. What if? What if he had left his wife and children, traveled to Hillsdale, married (or not) Rhoda Wiltse, had another 2 children (Ruth and Charles), and then joined the service to fight in the Civil War. And then I remembered something. Quite awhile ago, I checked the USGenWeb page for Hillsdale County, Michigan, which had a complete listing of all that county's volunteers. There was a Lewis Prosser listed in Co. G, 2nd Michigan Cavalry, but he was 17 at the time of his enlistment.. At this point, I didn't care how old this database said he was, I wanted his military records! I received them from my researcher at the National Archives, and they were an eye-opener: As it turns out, Lewis Prosser was 44 years old, born in Oneida County, New York, enlisted in Hillsdale, Michigan on 14 September 1862, and deserted in Nicholasville, Kentucky on 8 January 1863. He was "last heard from on his way to Canada."

I found him. There is lots more research for me to dig into - while I'm at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City later this month I'm going to look at all the records they have for LaPorte County. And since most of the county newspapers are still on microfilm, I may be stopping at the Michigan City Library on my way to Grand Rapids for the National Genealogical Society Conference in May. But, oh, joy of joys - I found him. Which proves what I've been saying for years: There is ALWAYS something more to find! |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

All content (c) Claudia Breland, 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed